MINNEAPOLIS — Editor's note: Some of the images depicted in the video and testimony are graphic. Have a question you'd like to hear our trial experts answer? Send it to lraguse@kare11.com or text it to 763-797-7215.

Tuesday, April 6

- Lieutenant in charge of use-of-force training said Chauvin's actions were not authorized

- 'If you don't have a pulse on the person, you will immediately start CPR,' said MPD officer in charge of first aid education

- LAPD sergeant took the stand as an expert witness: 'My opinion was that the force was excessive.'

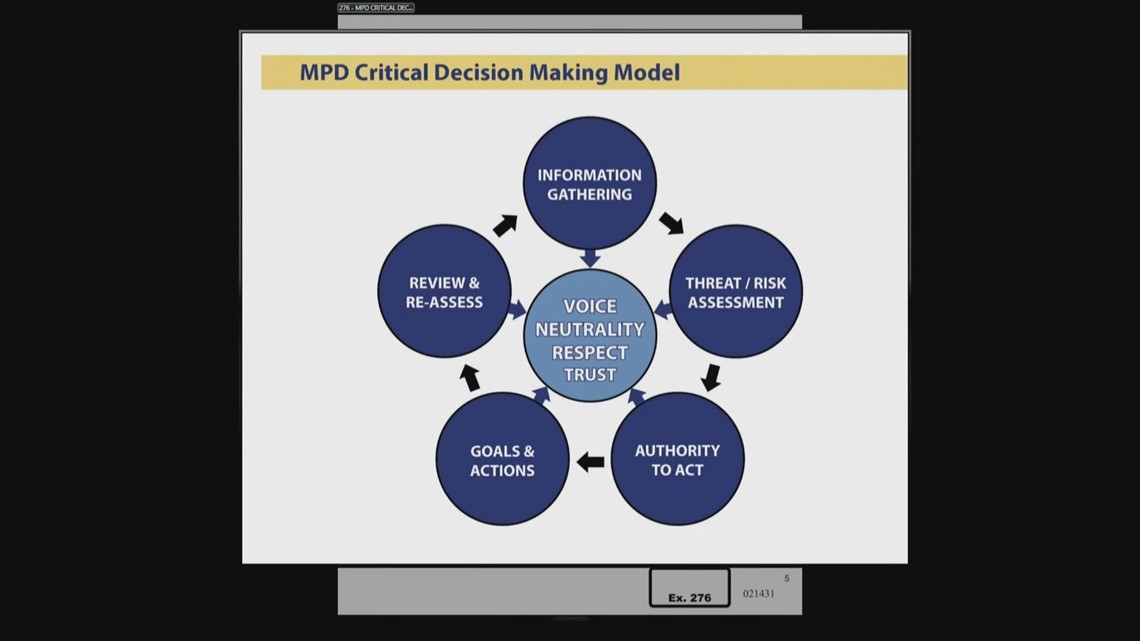

- Sgt. Ker Yang, head of MPD's crisis intervention training, described critical decision making model

- Judge said Morries Hall, who was with George Floyd when he was arrested, can testify on narrow topics without violating 5th Amendment

The second week of the Derek Chauvin trial continued Tuesday with more expert testimony surrounding authorized use of force by Minneapolis police officers.

Former officer Chauvin is charged with second-degree murder, second-degree manslaughter and third-degree murder in George Floyd's death.

The jury heard from Lt. Johnny Mercil, who was in charge of use-of-force training at the time of Floyd's arrest. Mercil said using a knee on a person's neck is not a trained MPD neck restraint, but "isn't unauthorized" when using force. He confirmed that once a person is handcuffed and under control, the technique would no longer be authorized.

Mercil acknowledged that Chauvin may have been drawing on other training about using his weight to gain control. However, he said officers are trained to avoid the neck and instead "put it on their shoulder and be mindful of position."

During cross-examination, defense attorney Eric Nelson asked Mercil if he has ever trained officers that if a person can talk, they can breathe. "It's been said, yes," Mercil said.

Officer Nicole Mackenzie also testified Tuesday, saying that officers are trained to provide CPR "immediately" once a pulse cannot be found. She also agreed with the defense that a crowd of bystanders could make it hard to administer CPR.

The state's first expert witness from outside the city of Minneapolis, LAPD Sgt. Jody Stiger, testified Tuesday afternoon. Stiger said after watching the videos showing Chauvin's restraint of Floyd, "My opinion was that the force was excessive."

Before testimony began Tuesday, the judge heard from Morries Hall, who wants to invoke his Fifth Amendment right not to testify because it would cause him to self-incriminate. Hall was with Floyd when he was arrested outside Cup Foods. The judge said he will hold a second hearing to go through a narrow list of questions that he believes are admissible, instead of allowing Hall to avoid testifying completely.

RELATED: MPD lieutenant in charge of use-of-force training says Chauvin's actions were not authorized

LIVE UPDATES

Tuesday, April 6

3:30 p.m.

Judge Peter Cahill abruptly adjourned court early Tuesday, after a private sidebar with the attorneys. He told the jury they will resume at about 9:15 a.m. Wednesday.

The day's proceedings ended in the middle of the prosecution's direct examination of expert witness LAPD Sgt. Jody Stiger.

2:40 p.m.

The prosecution called its fourth witness of the day Tuesday afternoon. Jody Stiger is a sergeant with the Los Angeles Police Department.

Stiger is the first expert witness who does not have a direct connection to the city of Minneapolis. From 2003-2007, he served as a "peer member" on the use-of-force review board for LAPD. He also worked as a patrol sergeant in LA's Skid Row neighborhood.

Sgt. Stiger said he has worked in the highest-crime neighborhoods in LA. He was a tactics instructor for six years, leading in-service trainings for thousands of officers. He is also a trainer for de-escalation and force options.

"The goal was for them to utilize their de-escalation tactics so they wouldn't have to use force," he said.

Stiger also reviews use-of-force incidents for the LAPD, and has consulted for other agencies as well.

As an expert witness, Stiger was paid by the state to review the videos of George Floyd's arrest and restraint, reports, and Minneapolis Police Department manuals and training materials.

Prosecutor Steve Schleicher asked Stiger his opinion of the force used by Derek Chauvin against George Floyd.

"My opinion was that the force was excessive," Stiger responded.

Stiger said when considering the severity of the offense, in this case a suspected counterfeit $20 bill, "typically you wouldn't even expect to use any type of force."

Sgt. Stiger testified that when Floyd was "actively resisting" the officers trying to get him into the squad car, the tactics used were appropriate.

"At that point the officers were justified in utilizing force," Stiger said. "However, once he was placed in the prone position on the ground he slowly ceased his resistance and at that point the officers, ex-officers I should say, they should have slowed down or stopped their force as well."

Stiger said that although he believed the officers' actions were "reasonable" when they attempted to put Floyd in the squad, there were alternatives.

He noted that it appeared Officer J. Alexander Kueng gained some rapport with Floyd early on, so "verbalization" would have been a good way to get him to comply.

Stiger testified that a person who is in the prone position may have trouble breathing and develop "positional asphyxia," which "may cause death." He said the person has to be moved into a side recovery position to allow them to breathe.

Prosecutor Steve Schleicher asked Stiger about a moment on body camera video where the officers discuss whether to use the "hobble" device, and then they decide not to.

"Based on my review I would believe that they felt that he was starting to comply and his aggression was starting to cease," he said.

2 p.m.

Defense attorney Eric Nelson cross-examined Officer Nicole Mackenzie after the prosecution questioned her Tuesday afternoon. Mackenzie is in charge of first aid education for all Minneapolis police officers.

Nelson read from a Minneapolis Police Department policy that states an officer should render medical aid "as soon as reasonably practical" after using force. Mackenzie agreed that officers should make sure the scene is safe first.

Nelson asked if bystanders and traffic could be factors in determining scene safety, and she agreed.

Minneapolis police officers are also required by policy to request EMS as soon as reasonably possible, Nelson added, based on what's going at the scene.

Nelson asked Mackenzie to describe "agonal breathing." She said it is not the same as effective breathing.

"It's kind of an irregular gasp for air," she said. "Your brain's last-ditch effort to pull in some air."

Mackenzie acknowledged that an officer could mistake this for effective breathing, but said MPD trains officers on the difference. However, she acknowledged a noisy environment could make it harder to tell.

Nelson asked Mackenzie several questions about her experience with fentanyl and drug overdoses.

Mackenzie confirmed that officers are trained in administering Narcan, and in a condition called "excited delirium."

She said there is a one-hour block of instruction on excited delirium, which she said can be a combination of psychosis and agitation. She said the course teaches officers to recognize it as a medical condition, not necessarily a criminal matter. Usually illicit drugs are a "contributing factor," Mackenzie said.

Nelson asked what signs officers are taught to look for. Mackenzie listed elevated body temperature and taking off clothes. "Their heart rate might be extremely elevated and they might be insensitive to pain," she said. "Because you don't really have that pain compliance that would normally otherwise control somebody's behavior, somebody experiencing this might have what we call superhuman strength."

Dr. Bradford Langenfeld, the ER doctor who pronounced Floyd dead, testified Monday in the trial. He called the diagnosis of excited delirium "controversial," and said he did not believe that was what Floyd was experiencing when he came into HCMC.

When asked to describe the term "load and go," Mackenzie said sometimes it may make more sense to bring a person directly to the hospital rather than administer CPR on the scene. She gave an example of a person with a knife in their chest, who needs immediate surgery.

Nelson asked her if bystanders could prompt a "load and go," and she said yes.

"Sometimes getting out of the situation is the best way to defuse it," she said.

She said it's difficult to focus on CPR while there's a crowd.

"If you don't feel safe around you, if you don't have enough resources, it's very difficult to focus on the one thing in front of you," she said.

Nelson asked if the distraction can harm the patient. "Yes," Mackenzie responded.

Upon redirect, Mackenzie confirmed officers are trained that sometimes they need to provide medical aid in "less than ideal conditions."

"That would be a growing contingent of people around, if they're yelling, being even verbally abusive to those that are trying to provide scene security," she said. "If there's people trying to interfere with the crime scene, or interfere with the patient."

She said an officer may be excused from rendering aid if they were being "physically assaulted."

The judge dismissed Mackenzie early on Tuesday because of a legal issue surrounding her testimony about excited delirium. Cahill said she will be called back during a different part of the trial.

1:30 p.m.

Officer Nicole Mackenzie took the stand Tuesday afternoon. Mackenzie is the medical support coordinator for the Minneapolis Police Department.

Mackenzie said her primary responsibility is first aid education for new officers and current officers. She also trains officers on the use of Narcan, administered in the event of an overdose.

She started as a part-time trainer in 2017, and accepted the full-time position in January of 2020. At a minimum, Mackenzie said officers are trained every year on CPR and AED use.

Officer Mackenzie walked the jury through a model she teaches officers to help them determine if someone is responsive.

- Alert

- Verbal

- Pain ("a little pain stimulus" such as pinching someone's finger)

- Unresponsive

If officers determine someone is unresponsive, they move onto addressing the ABCs: Airway, breathing and circulation.

"If you don't have a pulse on the person, you will immediately start CPR," Mackenzie said.

Prosecutor Steve Schleicher asked Mackenzie if she trains officers that if a person is talking, they can breathe. That comment was made by the defense during questioning of the previous witness, Lt. Johnny Mercil, who responded "it has been said."

Mackenzie said she does not tell officers this because it is "incomplete." She said someone could be in "respiratory distress" and still be able to verbalize it.

"Just because they're speaking doesn't mean they're breathing adequately," she said.

10:15 a.m.

Lt. Johnny Mercil with the Minneapolis Police Department was the second witness called to the stand by the prosecution on Tuesday.

Mercil became a part-time use of force instructor back in 2010. He also introduced Brazilian jiu-jitsu training to the department. Mercil described it as "a form of martial art that really focuses on leverage and body control."

He said it includes using "pain compliance" techniques.

Mercil was in charge of use of force training for MPD during the time of George Floyd's death last year. Mercil said he was also in charge of reporting officers' completion of required trainings to the POST (Peace Officer Standards and Training) Board.

Prosecutor Steve Schleicher asked Mercil to talk through a deck of slides from a 2018 defensive tactics training, which Chauvin attended.

Mercil pointed out a slide that mentions the sanctity of life and the protection of the public. "That is the cornerstone of our use of force policies," he said.

Mercil said the use of force is defined as any weapon, vehicle or tool that causes pain or injury; physical strikes to the body; physical contact that inflicts pain or injury; or restraint likely to produce injury.

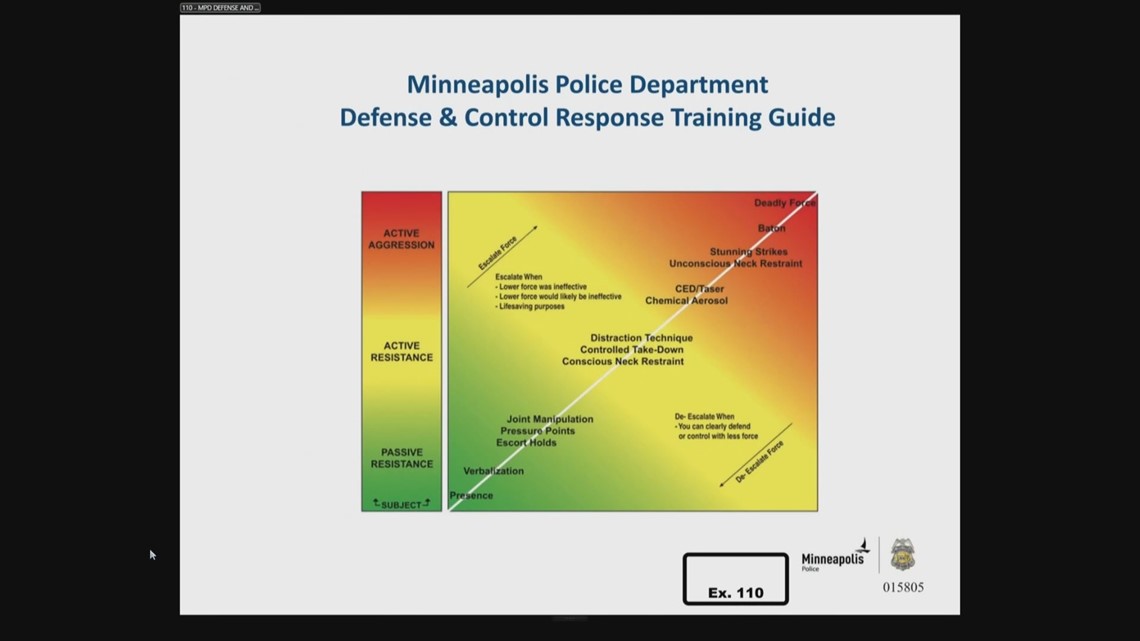

He also explained the concept of "proportionality" that he teaches officers.

"You want to use the least amount of force necessary to meet your objective," he said. If the lower levels do not work or are "unsafe to try," officers may use a higher level of force.

Mercil also explained the use-of-force continuum, which shows the amount of force that may be appropriate as the level of resistance increases.

Schleicher also asked Mercil to read from Minnesota statute 629.32, which is included in the training. It says, "A peace officer making an arrest may not subject the person arrested to any more restraint than is necessary for the arrest and detention."

The prosecutor showed Mercil a photo of Chauvin with his knee on Floyd's neck. Mercil confirmed that it showed a use of force.

Schleicher also pulled up a training slide that warns officers about parts of the body that are more vulnerable to serious injury or death. The "red zones" include the head, neck, throat, spine, kidneys, tailbone, sternum and solar plexus.

Mercil confirmed that neck restraints were permitted by the Minneapolis Police Department at the time of Floyd's arrest. Conscious neck restraints could be used to gain control of a person, or an unconscious neck restraint could be used by "applying pressure until the person, when they're not complying you can put enough pressure that they become unconscious, and then they're complying."

Those restraints could be done with an arm or a leg, Mercil said. He said MPD may show younger officers what it looks like with a leg, but as far as he knows, they have never trained officers to use their leg in a neck restraint.

Schleicher showed a slide that tells officers a conscious neck restraint is "OK on Actively Resistant Subjects." An unconscious neck restraint, however, is only applied:

- On subjects who are exhibiting active aggression, or;

- For life saving purposes, or;

- On subjects who are exhibiting active resistance in order to gain control of a subject and if lesser attempts at control have been or would likely be ineffective.

The slide includes a note that says neck restraints "shall not be used against subjects who are demonstrating passive resistance as defined by policy."

Schleicher showed Mercil a photo of Chauvin with his knee on Floyd again. "Is this an MPD trained neck restraint?" he asked. "No, sir," Mercil responded.

"Is this an MPD-authorized restraint technique?" Schleicher asked.

"Knee on the neck would be something that does happen in use of force that isn't unauthorized," Mercil said. The length of time authorized would depend on the "type of resistance," he said.

If the person was under control and handcuffed, Schleicher asked if it would be authorized.

"I would say no," he said.

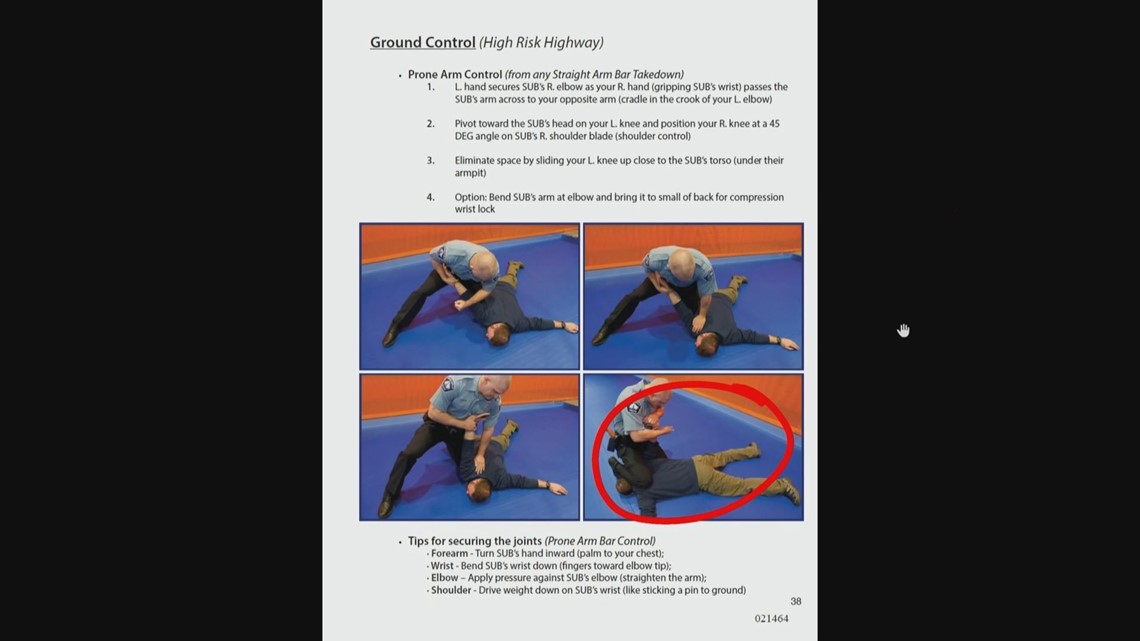

Mercil said when handcuffing a person in a prone position, the knee is often used on the shoulder blade. "Control doesn't end with handcuffing always," he said.

He said it would be appropriate for the officer to remove their knee once the person is no longer resisting. Mercil also said the person should be placed in the side recovery position, or the officer should have them sit or stand up.

"There is the possibility and risk that some people have difficulty breathing when their hands are cuffed behind their back and they're on their stomach," he said.

That should happen the "sooner the better," Mercil said.

Mercil also discussed the "maximal restraint technique." He said the only authorized way to use this position, as far as he knows, is with a device called a hobble. He said in this situation, the side recovery position should also be used "as soon as possible."

Lt. Mercil said that the act of reassessing is "paramount to the use of force."

Defense attorney Eric Nelson cross-examined Mercil, beginning by asking him about the "ground defense program."

"It's using techniques other than strikes to control individuals," he said. Mercil said he helped to introduce the program 10 years ago, and it includes jiu-jitsu and body control.

Mercil agreed with Nelson that sometimes officers have to do things that are unattractive, and that being a police officer can be a dangerous job.

Nelson asked Mercil if he's had people say they're having a medical emergency or "I can't breathe" while they're being arrested. He said yes. Nelson asked if there have been times when Mercil did not believe the person, and he said yes.

Mercil acknowledged that a subject may be compliant and then later become noncompliant. He also said officers can consider a large size difference when deciding how much force to use. He said the influence of controlled substances can be a factor as well.

A chokehold is defined as blocking the airway or trachea from the front, Mercil confirmed. He said he did not see Chauvin use a chokehold on any of the video he reviewed.

Mercil said the amount of pressure that an officer would need to apply to an individual to render them unconscious varies. He said a person being on controlled substances or having an adrenaline rush may speed up the process. He said in his experience, a neck restraint can render someone unconscious in "under 10 seconds."

Lt. Mercil acknowledged the MPD tells officers during training that a person could become combative afterward, but said, "I have not experienced someone fighting after a neck restraint."

Mercil also confirmed that an officer can hold someone after they become unconscious.

"You can have your arm around their neck for a period of time, yes," he said.

When Nelson asked if they could be held until EMS arrives Mercil said, "I wouldn't go that far."

Mercil acknowledged that an officer has to decide if it's "worth the risk" to take handcuffs off and render medical aid to a person who's restrained. He said other safety factors including the crowd and being on a busy street could factor into the decision making model.

Lt. Mercil said that while the technique Chauvin used was not a trained neck restraint, he may have been following the training of using body weight to gain control of a person. However, Mercil said, MPD trains officers to stay away from the neck when possible, and "to put it on their shoulder and be mindful of position."

Nelson showed Mercil a training photo that shows an officer restraining a person. Mercil said in the photo, the knee is on the shoulder, not the neck.

Nelson showed Mercil a series of body camera images from officers restraining Floyd. He confirmed that Chauvin's knee appeared to be between Floyd's shoulder blades while the EMT checked for a pulse.

Mercil said he has held a person using his body weight until EMS arrived. Nelson asked if he trains officers to do this. "As long as needed to control them, yes," he said.

Nelson asked if Mercil has ever trained officers that if a person can talk, they can breathe.

"It's been said, yes," Mercil said.

Nelson pulled up the use-of-force continuum again, showing that joint manipulation, pressure points and escort holds can be used if a person is passively resisting.

Upon redirect, prosecutor Steve Schleicher asked Mercil to confirm that a knee on the back is a "transitory" position, meant to gain control. Schleicher asked if it would be appropriate to hold someone in a prone position with a knee on top of them after they have stopped resisting, and Mercil said no.

Mercil also confirmed that he has never seen a restrained person lose their pulse and then come back to life.

After both attorneys finished questioning Mercil, the judge ordered a recess until 1:30 p.m.

9:30 a.m.

The state called Minneapolis Police Sgt. Ker Yang to the stand as its first witness of the day Tuesday. A 24-year veteran of the department, Yang is the crisis intervention training coordinator for MPD.

Yang defined "crisis" as anything that is beyond a person's coping mechanisms. He said in the training, Minneapolis police officers are taught to recognize signs of crisis, and to bring the person back down to a pre-crisis level.

Yang talked through the "pillars of procedural justice" described in the Minneapolis critical decision making model: Voice, neutrality, respect and trust.

The model then describes the following steps:

- Information gathering

- Threat/risk assessment

- Authority to act

- Goals and actions

- Review and re-assess

And then the cycle continues, going back to information gathering.

Yang said the ultimate goal in a crisis situation is "to see if that person needs help." He said the officer should be constantly re-evaluating the strategy.

Yang acknowledged that sometimes officers are in fast-moving situations. He said sometimes, though, the opposite is true.

"A lot of the time we have the time to slow things down and re-evaluate, re-assess and ... go through this model," Yang said.

Defense attorney Eric Nelson cross-examined Yang after about 20 minutes of questioning from the state.

Nelson asked Yang to confirm that he was the one to introduce the critical decision making model and crisis intervention trainings. He said he did, with approval from the high-level management of the department.

"Police actions can look really bad," Nelson said. "But they still may be lawful, even if they look bad. Correct?" Yang said that is correct.

Nelson showed Yang a section of MPD training curriculum, asking him to list the potential signs of aggression officers are trained to look for in suspects or observers. Yang said that they are trained to look for things like "standing tall, red in the face, raised voice," and other signs.

However, Yang said the training he read from is presented to cadets and is different from what would have been presented to a veteran officer like Chauvin.

Yang confirmed that veteran officers are trained on the critical decision making model, and that they use it in "constantly evolving" situations.

8:30 a.m.

Before the jury comes in Tuesday, the judge is expected to hear motions about the testimony of George Floyd's friend, Morries Hall.

Hall was with Floyd when he was arrested, and the defense has asked several questions about Hall potentially selling opiates to Floyd.

Last week Hall pleaded the fifth, saying he will not testify in the trial. The Fifth Amendment allows someone the right not to self-incriminate.

Hall's attorney told the judge that Hall will be vulnerable to a third-degree murder charge based on the allegation that he sold Floyd drugs before his death.

Derek Chauvin's defense attorney, Eric Nelson, told the judge that he plans to ask Hall about his activities with Floyd on May 25, 2020, and whether he provided Floyd with any controlled substances, and why Hall left Minnesota immediately after Floyd's arrest and death.

Judge Peter Cahill decided that most of the questions Nelson wanted to ask could incriminate Hall, and therefore those topics should be avoided.

However, Cahill said Hall should be able to testify on the narrow topic of George Floyd's condition when he was back in the car outside Cup Foods, and whether he fell asleep suddenly.

"I don't see how that would put him closer to criminal liability, just from those observations," Cahill said.

Cahill asked Nelson to draft a list of potential questions by Thursday. He said then Hall can have a chance to meet with this lawyers and they'll hold another hearing to walk through the permissible questions.

"We need to tread carefully," Cahill said. "The Fifth Amendment right is a broad one."

Monday, April 5

In the Hennepin County Courthouse Monday, jurors heard from three of the prosecution's expert witness: Dr. Bradford Langenfeld, who said that he tried to resuscitate George Floyd in the emergency room on May 25, 2020, Katie Blackwell, an inspector of the Fifth Precinct and commander of the MPD training division, and most notably Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo.

Arradondo was on the stand for most of Monday, and said after reviewing all of the video footage, he believes Chauvin's actions violated MPD's policies on de-escalation, use of force, and rendering medical aid to a person in custody.

He said while it is important that his officers get home safe at night, it is also important that their community members get home safe.

"Of all the things that we do as peace officers for the Minneapolis Police Department," Arradondo said, "It is my firm belief that the one singular incident we will be judged forever on, will be our use of force."

After hearing from the chief, jurors heard testimony from another member of the MPD, Inspector Katie Blackwell. Prior to January of this year, she was the commander of the MPD training division.

Blackwell said she has known and worked with Derek Chauvin for about 20 years.

When prosecutor Steve Schleicher showed her a picture of Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd's neck outside of Cup Foods, she confirmed that it was not consistent with MPD training.

Blackwell testified that per policy, a neck restraint is compressing one or both sides of the neck using an arm or leg. But MPD trains officers to use one arm or two arms.

"I don't know what kind of improvised position that is," she said. "So that's not what we train."

Judge Peter Cahill said after hearing from a training sergeant on Friday and the two officers who spoke Monday about Chauvin's use of force, the state may need to stop focusing on that topic.

"We are getting to the point of being cumulative," Cahill said. "You're not going to be able to ask every officer, 'What would you have done differently?'"

The first witness for the state on Monday was the ER doctor who treated George Floyd when he arrived at the hospital on May 25.

Dr. Bradford Langenfeld said that he did not receive any report that officers had attempted to give Floyd CPR, and that the paramedics who brought him in did not mention a potential drug overdose or heart attack. Those are among the possible causes of death that Chauvin's attorney plans to use in his defense.

The doctor noted that Floyd's heart was barely beating when he arrived at the hospital, and testified that Floyd was in PEA, or Pulseless Electrical Activity, which he said can suggest hypoxia, or low oxygen.

Langenfeld said he felt that hypoxia, or "oxygen insufficiency" was more likely than a drug overdose or heart attack as the cause of Floyd's death. "Asphyxia" is another commonly used term.

Once Dr. Langenfeld determined that they could not resuscitate Floyd, he pronounced him dead.